Elephants to Einstein

GA 352

IV. The Human Eye. Albinism

2 February 1924, Dornach

Gentlemen, the question that has been asked is:

Is the iris of the eye a mirror of soul life in sickness and in health?

I think the second question can be combined with it; they are probably meant to go together:

How does albinism or leukopathy develop in black people?

To answer this question we must above all consider the nature of the human eye in some detail. The question has to do with the fact that some people draw conclusions as to the sickness or health of the whole body from the state of the iris, the coloured ring-shaped structure surrounding the blackness of the pupil in the eye. The iris does indeed show the greatest imaginable variation in different people. As you know, it is not merely that it is blue or black or brown or grey or indeed hazel, but it also has lines created by tiny vessels that run in different patterns. It is true, therefore, that just as the general facial features differ from person to person, so the more subtle structures of this iris or rainbow membrane differ greatly between people, much more so than the facial features differ from person to person.

We'll need to go into the structure of the eye to some extent if we want to talk about the subject. This also relates to the other question you have asked. It is that especially in negroes but also in others who are not black, the skin shows abnormal, unusual colouring and this is connected with the special colouring of the iris. It is in a way connected. The skin colouring is particularly striking in black people for the very reason that the rest of their skin is black, and they then have all kinds of white spots, looking mottled like a tiger. They are only rarely completely pale and completely white; that is extremely rare among negroes, extraordinarily rare. But 'albinos', as they are called, may also be seen in races that are not completely black in colour. Albinism also occurs among white people; they have a very pale skin, an almost milky white. The iris is usually a pale reddish colour, with the pupil, which is black in other people, a dark red. A female albino I once saw was showing herself in all kinds of fair booths. The skin was milky white all over, the iris red, with dark red rather than black pupils, and she said in an uncommonly weak voice: 'I am entirely white, have red eyes and have very poor vision.' And that was true, she could not see well.11Translator's note. Rudolf Steiner handled the gender of this person in an unusual way in the German. 'Albino' is a masculine noun in German. It is, however, normal usage to change to the feminine gender for any pronouns that follow if the individual is female. Rudolf Steiner did not do so. The text thus reads: 'was showing himself in all kinds of fair booths ... and he said ... he could not see well.' Rudolf Steiner was also using a term for an albino that was then colloquial in German: Kakerlak, meaning 'cockroach', which no doubt arose because cockroaches are also very sensitive to light.

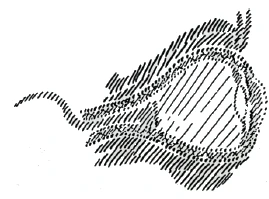

If we want to go into the matter we must first of all study the structure of the eye itself. I have been telling you various things in the course of time, and so you will probably be able to understand what I am going to say today. You see, the eye lies in the extremely solid bony part of the head. The bony form of the head arches in there (Fig. 6) and the eye lies in this bony cavity, which is opening towards the brain here at the back. The outer border of the eye to the outside is a hard membrane, which is not transparent here. The eyeball, as it is called, is enclosed in a firm membrane, the external tunic. This becomes transparent at the front, here, where it bulges a little. We would not be able to reach the light with the inner part of the eye if that part of the membrane were not transparent. It is called the cornea in its transparent part because it is hornlike. Next to it to the inside is a membrane consisting of fine blood vessels. The body's blood network extends to the eye, sending extremely fine capillaries into the eye. So we have here the external tunic, which is transparent at the front, and lying close to it the choroid, as it is called. The third membrane inside is made of nerves; it is called the retina. So I have to draw in a third membrane, the retina. This extends backwards, as does the choroid. And this, being nerve substance, going in the direction of vision, is called the optic nerve. You know how people say that we sense things through the nerves. And with the optic nerve we see.

The strange thing is, however, and everyone has to admit this, that we see with the optic nerve in all these parts, but not in the place where it enters; there it is blind and one sees nothing! If someone were to look in such a way that he would be looking just there, somehow, or if the nerves all around were to be diseased and only the place where the optic nerve comes it was healthy, one would nevertheless see nothing at the place where it comes in. Now people say: 'We see with the optic nerve; it is there so that we may see.' Have you ever heard the following? Imagine a group of, say, 30 workers; 25 of them must work busily. They stand all around there. And then there is a group of 5—it is not the kind of thing one does, but let us suppose it is done like that—and these 5 are allowed to be idle while the others are working hard. So we may say these are the 25 busy workers and there we have 5 who are idle all the time, sitting in comfortable armchairs and doing nothing. If someone were to tell you that the work is just as much done by the 5 idlers—or perhaps he cannot say this, because he does not see it, but the work is done by people being idle—you would not believe him, would you? It is clearly nonsense. But scientists tell us: 'The optic nerve sees.' Yet in the very place where there is most of this nerve it does not see at all! That is just as if you were to say the work is being done by the 5 idlers. You see people actually know these things—that is what is so odd about it—but they will insist on their common or garden nonsense. I think you'll agree that the existence of the blind spot, for that is what it is called, here where the optic nerve comes in most strongly (Fig. 6) and the fact that we do not see anything whatsoever in this spot shows quite clearly that the optic nerve cannot be something we see with.

The matter is like this. There is something in the human body that is very similar to this business with the optic nerve; and that is your two arms and hands. Imagine you pick up a chair. You make a great effort with your arms, including your hands. But the element that connects them remains up here, does it not? It is the same with the optic nerve. You endeavour to do something that reaches out to the light, and in the middle it is just the way it is between the two areas where your arms attach here. But it is not the optic nerve which reaches out—if it were the optic nerve it would have to see most exactly in that spot—but what reaches out is part of the entirely invisible element that I have described to you. This in fact is indeed the I, the I-organization. It is not the physical body, nor the ether body, not even the astral body; it is the I. And so I have to draw in something else, apart from what is already in there: it is the invisible I which spreads there. Except that it is not as if there were two such arms but as if the two arms were to come together and make a sphere. We create part of a sphere when we touch something with our hands. That is how the supersensible I is in there; it takes hold there. And what purpose does the nerve have? Well, gentlemen, the nerve is there—this being work done by the invisible human being—so that secretion may happen. Matter is secreted everywhere and remains lying everywhere. We see with our supersensible I. But the nerve is there so that something may be secreted.

Consider the nonsense scientists talk. It is as if one were to examine the colon and whatever is inside the colon and one would actually say that human beings take their nourishment from the material excreted from the colon! Just as you have matter in the colon which is then excreted, so nerve matter is excreted here. And this (the blind spot) is the place where most of it is excreted. Material not needed in the eye is excreted into the brain and then goes further and is eliminated altogether. You see, this is something you can understand quite easily, yet people tell the weirdest tales about it today. It is simply that people do not realize what it means when others insist that we see with our nerve substance or have sentience or perceive something or other. That would be the same as if we were to take our nourishment from the contents of the colon. So you see that this matter of the blind spot has no significance for the ability to see, for the optic nerve around it does not see either; it is merely that here, where the blind spot is, most matter is excreted. And just as nutrition comes to an end in the colon, and this exists only for the purpose of elimination, so does vision come to an end here, for this is where most is eliminated, and there also is no point to being able to see there in the middle.

Imagine a stick lying there and you were to try and pick it up with your head! You cannot do it. You have to pick it up with your arm, your hand, with something attached to you at the side. In the same way you cannot see with the nerve. You have to see with something that reaches out. Now, gentlemen, everything you have there (Fig. 6) ends here in a kind of muscle. This muscle holds the lens. That is a completely transparent body. Why transparent? So that we may get to the light. And behind this body is a thickish liquid. In front is an even thicker liquid, and in this thickish liquid floats the iris, which lies here, close to the blood vessels. It really floats in the liquid, leaving a hole for the light. This hole looks black when you look into it, because you are looking right through the whole eye to the back of this, which is black.

The iris is fairly transparent in front and black at the back. The black membrane at the back is fairly thin in some people. Some people have blue eyes because one is looking through something transparent into blackness when it is thin. And the eyes are black or dark in people who have a thicker membrane, where you are looking at a thick skin at the back of the iris. We'll talk about brown eyes shortly.

We have to consider why it is so, gentlemen, that this membrane, which really is responsible for the blue or brown or black, is thicker or thinner in some people. I have told you that there, into the eye, goes what we call the I, this most sublime supersensible part of the human being. There the I enters. The I is strong or weak to a different degree in people. Take it that the I is very strong in a person, that a person has a very strong I. You see, such a person is able to dissolve the iron he has in his blood—through this choroid membrane it also gets into the eye—completely. Someone who has a strong I thus dissolves the iron completely, and the result is that very little iron gets into this membrane, which after all is in the outermost margin of the body, because it has been completely dissolved. Little iron gets into it, and the result is that this membrane becomes thinnish. And because it becomes thinnish, one has blue eyes. Now imagine someone has a weak I; he then does not dissolve the iron so much, and the result will be that a great deal of undissolved iron still gets into this membrane. This undissolved iron makes the membrane thicker, and a person has dark, black eyes. It thus depends on the I whether a person has black or blue eyes.

Well, gentlemen, there is also another substance in the blood, and that is sulphur. Even if the I is able to deal with the iron, it is sometimes unable to deal with the sulphur. When the I lets undigested sulphur enter into this membrane, a yellowy brown develops in the iris, and a person has brownish eyes. If especially large amounts of sulphur get into the eyes, the iris will be reddish. Even the pupil is not black in that case, because of the sulphur that shimmers behind it. That is the case with albinos, with people who also cannot properly provide their skin with colour. We may say, therefore, that there are people who can inject sulphur into their eyes, as it were. The I can inject it, and this produces the unusual colouring of the iris.

But anything that gets into the eye by way of sulphur or iron also gets into the whole body, for it comes from the blood. Those are just tiny blood vessels here in the eye. If someone injects sulphur here in the eye, he also injects sulphur into the whole of his skin everywhere. And the result of thus injecting sulphur everywhere into the skin is that he does not have the natural skin colouring in these places where the sulphur has been injected; for our natural skin colour comes from iron being processed. If someone therefore only processes his iron slightly and injects sulphur instead, he gets those patchy skin areas and one can at the same time also see it in the eyes.

So you see, it is exactly when we consider this invisible human being who is present in every person that we can understand the human being right down to the level of physical matter. Anthroposophy is not so idiotic that one cannot understand matter. It is the materialists who actually do not understand matter. If you read about albinism anywhere—what do your read? The one among you who has asked the question will probably have read somewhere that the cause of albinism is unknown. Materialists arrive at this strange statement that the cause is unknown because they pay no heed at all to the situations where the causes are to be found. It is of course easy to say: That is a red pupil. Yes, but one must know what is really at work in there, and what is injecting the business, for both the red and the pale colouring of the body come from the sulphur.

Now you'll be able to understand the nature of true science. Imagine you go somewhere on earth where some work has been done. Someone looks at it and says: 'The work is there, the cause is unknown.' He does not care about what happened before. He therefore says: 'Cause unknown.' The fact that 30 people have been working there for many days, for example, does not concern him. That is what scientists do when they say the cause of the red hue of the pupil and the pale hue of the skin is unknown. But the cause lies in the I which is at work there in the physical matter.

You also see from this that the iris does indeed have something of a true mirror image of the way the whole body works with iron and sulphur. But just take such an albino. That is really a kind of illness. Too much work is done with sulphur in the body, but the body gets used to it and things are organized that way. Now it may happen that the degree to which this gets into the eyes is much less. You see, apart from the albino lady who was showing herself in a fair booth, I have seen quite a few other albinos. And it is always possible to show that there is a very special situation with such albinos. You may say: 'There's an albino, and he has this unusual red colouring of the iris, a pale red, with the pupil dark red, and has a pale body.' If you now examine him further you come to see, from the nature of his body, that the connection between heart and kidney is particularly weak. The kidneys are only supplied with blood with great difficulty and therefore only function laboriously. If this person were to deposit the sulphur which he has in him because of the nature of this whole body in the kidneys, he would die in childhood. He therefore gets rid of the sulphur by pushing it into the body surface—the skin gets white, the eyes are red—so that the kidneys can work delicately. Those albinos have the most delicately functioning kidneys, for instance. The same may happen in other people. But when people who are not albinos—most of them are not albinos—develop any kind of kidney defect, surely this must also show itself in the iris? For anything sulphur and iron do with one another is also reflected here. And so it is possible to see from this subtle reflection in the iris if there is a spot here or here that is not really normal: there you have damage in the body. But you have to consider, gentlemen, that the human body is a whole, and if one were clever enough to do this one could also see what is seen in the iris if one cut out a little bit of skin. Then something abnormal would also show itself in the skin, or in the nail of the big toe if one were to cut it off. There, too, you have very subtle distinctions, and you would be able to see from this that the liver or the kidney or the lung are not all right, though it would be a little bit different again. But if someone were particularly clever and examined cut-off fingernails rather than the iris, for example—it would be much harder because it is less obvious—he would also be able to see if the body is healthy or sick. It is noticeable in the eye simply because the eye is a particularly delicate structure, and subtle changes are easily perceived there. But you can see in other ways, too, that things emerge most strongly on the body surface. I have rarely seen someone wanting to get the feel of a very fine fabric or something like that put it on his shoulders. If this were to be the better method, we would of course arrange things in such a way that if we wanted to get the feel of something very fine we would bare the area up on the shoulder and touch and feel it there. But that does not get us anywhere. We feel it with our fingertips. And in the fingertips we are particularly sensitive to get the feel of things. So there we have the same again as before. If it were the nervous system that really allowed us to feel things, we ought to feel things most up there, close to the brain. But we do not have the strongest sense of touch close to the brain but furthest away from it, in the outermost fingertips, because the I is most of all located on the body surface. It is easiest to see what someone is inwardly, as an I, from the outermost surface. And because the eyes are most of all on the surface, this is also where one is most able to see these things, because the eyes are delicate and away from the brain.

You may say the eyes are in the skull and close to the brain. But we have many bones there to make sure they are really far away, and at the point where the eye connects with the brain, where there is no bone, nothing is seen at all. In the case of the fingertips it is therefore due to the distance in space that they are particularly sensitive; in the case o the eyes it is because they are most strongly shielded from the brain.

Something else is also strange. When a lower animal develops its brain, it does so in such a way that the brain leaves a cavity for the eye, and the eye does not grow out of the brain but becomes attached to the side there and grows into the cavity. The eye grows from the outside, not out of the brain; it grows into the brain. It is therefore produced from outside.

You can see from all this that whatever is produced on the surface, be it in the skin, be it in the eye, has to do with something that most closely connects the human being with the outside world. If someone always stays in bed, unable to use his will for the body, we cannot really say that he strongly develops his I. If someone is very mobile, we can indeed say that he brings his I strongly to expression. And it is the senses that apart from this keep us in touch with the outside world—in our smelling, seeing and so on. And the eye is the most delicate of senses to keep us in touch with the outside world. So we may well say that because the I is particularly active in this fine network of capillaries (those are terribly fine vessels in the iris) we can see a great deal from it—how the whole I works in an inward direction, that is, if a person is healthy or sick.

This is the first truth and insight we have relating to this matter. But this fact which I have been describing to you is also one of the most difficult, for one has to be extremely well informed as to what a minor irregularity in the iris may signify if one is to draw conclusions about a person being healthy or sick. Let me give you an example. You see, it may be, for example, that small dark dots appear here and there in someone's iris. These dark dots mean, of course, that the person has something which is not there if there are no dark dots in the iris. But let us assume this person, in whom the dark dots appear, is a terribly stupid fellow. He will then have some kind of illness that is indicated by those dots. But it may also be that the person who has those dark dots had excessive demands made on him in his youth to learn things, and this learning process went beyond his physical powers. The fact that he used certain organs too much in his youth may have driven a certain weaker activity into his eyes, and it may then happen that these small, fine iron deposits appeared due to overexertion in his childhood. They may thus appear due to illness in later life, but they may also appear due to overexertion in childhood. Most people tend to think: if I see little black dots in the iris then one thing or another must be the case in the body. It is, however, important to know not only about the person's present life. Particularly if one wants to look at such things in order to discover the causes of illness one must go through such a person's whole life with him; one must make him remember what he did on one occasion or another in his childhood. What we see in the iris may thus point to a number of things. And it requires extremely complex knowledge to draw any conclusions from this.

This is why it is so annoying when people write all kinds of pamphlets today. The things they write are usually quite brief, under the title of 'eye diagnosis'. You get 50 pages of instructions on how the iris should be examined. Like this, you see: there is the divided-up iris, there is the pupil, a completely schematic representation. Then it says 'disease of the spleen'; 'lung disease', 'syphilis' and so on. An eye diagnostician who knows what can be seen when he looks at the iris through a medium magnifying glass then only needs to refer to his booklet. And when he sees markings in the area where it says lung disease, he will say: 'lung disease'! And that is what many eye diagnosticians do today, after just an hour's study. They leave the rest to the booklet they have; they just make the diagnosis. Gentlemen, that is disgusting! You have something extremely difficult and these people want to learn it in the easiest possible way. The result is not something of value but quite the opposite. Damage is done to the whole field of medicine. And people must make the distinction between someone who has serious intentions in medicine or merely wants to make money.

People are of course upset about science today, rightly so, for if you take the example of the optic nerve I have given you, scientists pay no heed to what the human being really is but appreciate the excrement above all else in the human being, that excrement in the eye, for example, that is the optic nerve. People do not know this, of course, but they feel it, and get annoyed with scientists. One can understand their annoyance. But what eye diagnosticians generally do is not better than science but generally much worse. Out of ignorance, knowing no better because of modern materialism, scientists believe excrement to be the most sublime part of the human being. Excrement is, of course, most necessary, for if it were to remain in the body it would soon kill the body; it is therefore necessary. But scientists consider excrement to be the most valuable thing in the human being. But they are taking a right and proper course, for they do not just want to make money. It is just that they are struck with blindness. They have a very large blind spot in their knowledge; yet in spite of it all we have to acknowledge their good will. But when it comes to those eye diagnosis pamphlets, we cannot speak of good will, only of a desire to make money. So you always have to say to yourself with such things: a good truth may be at the heart of some endeavour, but it is exactly the best truths, gentlemen, that are most abused by the world. You see, it is truly marvellous that the whole human being in health and sickness is indeed reflected in the iris. But on the other hand the iris is hardest to diagnose for its own condition just because the whole human being is reflected in it in health and sickness, and we really have to say that anyone who does eye diagnosis without real knowledge of the whole human being is doing mischief.

What does it mean, to know the whole human being? You see, we have learned that the human being consists of his physical body, the ether body, the astral body and the I. One therefore not only has to know something of the physical body but must also know something of the spiritual human being, especially if one wishes to do eye diagnosis. You know, ordinary anatomy, which is only concerned with the dead body, may sometimes be adequate in what it has to offer; it may still offer something quite good, relatively speaking. Anatomists may not know that the optic nerve is the excrement of the eye, but they do at least find the optic nerve. But an eye diagnostician usually has not the least idea of how the nerve runs. He has his 50-page booklet showing divisions of the iris and diagnoses away; he does not examine the person. Then he'll of course need some other booklet, again of 50 pages. There the rubric ‘lung disease’ may be found and the remedy for it. But lung disease is something that may be from many causes. Knowing that the lung is affected does not tell us much. The lung affection may come from the digestion. One needs to know where it comes from. Many people have lung disease. In many of them the lung disease has a wide variety of causes. This is exactly where one has to be tremendously careful, for where you get the best things you also have the greatest mischief done. I told you often in these lectures that the human being depends not only on the earth but on the whole of the starry heavens. But that is exactly also what calls for the most complex insight. And one should not cause mischief here. Fraud and mischief are practised on a large scale by the different astrologers in the world today. It is much the same with eye diagnosis as it is in astrology. In astrology, one also has something sublime and magnificent. But there is nothing very sublime about the people who do astrology today. In most cases designs on other people's purses are the basis of their work.

And so you can see the connection, gentlemen. On the one hand we have phenomena that change the whole surface of a person, even externally. The person develops pale skin areas, the rest of the skin being darker, his eyes get a different colour; he is an albino. A certain activity is driven to the surface, deflected from the internal organs. But when someone is not an albino, the same things, the external appearance of the eye, are present in the iris, but the finer structure, the finer differentiation points to the inner organism. An albino is not totally ill from being an albino, he merely has the disposition for a disease because he has this from his young days and his bodily organization later gets used to it.

You see it is not good to call an albino a leukopath. It suggests that the blood of such people is different, leukocytes being particular corpuscles in the blood. The cause is not known. But when the blood grows paler on the surface, you do not get general green-sickness or anaemia, but the skin gets paler on the surface. That is the difference between the disease of green-sickness, where the blood inside simply gets paler, and leukopathy or albinism, where the blood is more pushed towards the surface. The situation is that when someone has anaemia, an internal function is out of order. The I is more active on the surface, the astral body more inside. Because of this, all the bodies we see or hear with are pushed more to the surface. We need those for the I. The liver we need inside. And if you were to feel everything your liver does as strongly as that, you would be observing your innards all the time, saying: 'Ah, I've just got some cabbage soup into my stomach, the walls of the stomach are beginning to absorb it. It is as though it radiates out, very interesting. Now it goes through the pylorus at the end of the stomach into the duodenum; it now reaches the villi in the intestinal walls.' You would take note of all this, and all of it would be most interesting, but you would have no time at all to take note of the outside world! It is very interesting and there is lots to observe, in many respects much more beautiful than the outside world, but human beings are quite rightly distracted from this. Generally speaking it does not come to conscious awareness; the things that are on the surface come to conscious awareness. If someone therefore does not digest the iron properly inside, where the astral human being is more active, he gets anaemic. If he does not properly deal with the iron outside, but dissolves it, as I have described it to you, he becomes an albino—which is very rare; he gets leukopathy.

So you see that the question I have been asked has to do with this: albinism is due to the I not digesting sulphur or iron in a regular way. Anaemia comes from abnormal iron processing by the astral body and affects more the inner part of the blood. And if one really understands what goes on inside the human being one can also see which supersensible aspect of the human being is involved. Someone with proper understanding of the physical human being also understands the super-physical, supersensible human being. But the situation with materialism is this: materialists do not understand the supersensible human being and therefore also do not understand the physical human being. I'll have them tell you if I'll be back next Wednesday. Maybe someone will have another question for the next session, so that we may have a similar discussion based on that question.