Elephants to Einstein

GA 352

VI. Human clothing

13 February 1924, Dornach

Good morning, gentlemen. Have you perhaps thought of something you would like to have for today?

Mr Burle: If one might ask Dr Steiner perhaps about human clothing, the garments people wear. In some countries people have just a rag that they wrap around them; others are buttoned up. One has shimmering colours, the other simple colours. Then one might also ask about the national costumes worn by a nation or by particular people. And also what waving flags are and—this may be connected with this-what ecstasy it causes?

Rudolf Steiner: Concerning human clothing—people have often thought, as you can imagine, why it is that there are so few documents and historical records about it. You see the clothes worn by simpler nations and tribes, and you also see the clothes worn by the people in the town where you yourself are at home. And finally one sees what one is putting on oneself, really paying least attention to the things one wears oneself. One simply goes along with custom in this. Indeed, to some extent one simply has to do this because otherwise one might be taken for half a fool if not a complete fool.

Now I think you'll agree the first question is the one that is probably hardest to answer for scientists considering only outer aspects, because, as I said, there are few written records about the reasons why people originally put on clothes. If you really consider everything that is available in this direction, you have to say to yourself: yes, much of what there is with regard to clothing has clearly come from people's need to have protection, the need to protect themselves from the influences of the environment. You must remember that animals have their own protection. Animals are very largely protected from external influences, which cannot get through their pelt, their skin, and so on and reach the more delicate, softer parts of the organism.

You may ask yourselves why people do not have such natural protection. I am not going to give too much consideration to this question, which is asking for the reason why, for with nature it is not really quite justifiable to ask the reason why. Nature simply puts the creatures there, and one simply has to study how they present themselves. The question why is never quite justifiable. But we'll understand one another if in spite of this I say: how come that man has to go about as he is, unclothed by nature?

Another question we must ask is whether the natural covering which animals have by nature does not clearly relate to the less advanced mental organization of the animals. And that is so. You see, gentlemen, it really is the case that sometimes the parts that are most important in a living creature, an animal and also in the human being, do not appear to be the most important to outer appearances. We can mention several organs in the human organism that are very small indeed. If they are not the way they are supposed to be the whole human organism breaks up. Here in the thyroid glands, for instance, tiny organs lie on either side—I have mentioned them in another context before13Parathyroid glands (epithelial bodies). Mentioned in lecture given on 2 December 1922. GA 348.—they are barely the size of a pinhead. Now one might think them to be less important. But if it should ever happen that someone needed a thyroid operation, a goitre operation, and the surgeon were clumsy enough to remove these tiny pinhead-sized organs as well, the whole organism would get sick. The individual would grow imbecile and gradually die of debility. Tiny organs the size of a pinhead thus have the greatest imaginable importance for the whole of human life. They have it because these organs secrete a subtle matter that must enter into the blood. The blood will be useless unless these organs are present and their secretions flow into the blood. You can see, therefore, that even organs to which one pays little attention in the whole system have the greatest imaginable importance for the individual in whom they are found.

Take animals with hairy pelts, for instance. Now you can imagine that a pelt is useful to prevent the animals being cold in winter, and so on. And yes, it is useful for this. But for those hairs to develop in the skin the animal must be exposed to very strong sun influences. The hair develops in no other way but that the animal is exposed to powerful sun influences.

Now you might say: 'Yes, but the hairs develop not only in the places that are reached by the sun's rays.' But it is true, nevertheless. It even goes so far that the human embryo is hairy in the early stages when it is carried in the mother's womb. There you may say: 'It is not exposed to the sun.' The embryo later loses that hair. Why is that so? It is so because the mother takes in the sun's influence and this is active inside her. Hair is very closely connected with the Sun's influence.

Take the lion, for example. Lions—and the males have that huge mane—are very much exposed to the sun. This also gives them chest organs that grow particularly strong under the sun's influence. The intestine is quite short, and the lungs are tremendously developed. The lion differs in this from our ruminants, in whom the organs of the lower body, intestines, stomach, and so on, are more developed. The way in which an animal has hair, feathers, and so on, thus relates above all to the sun's influence.

Yet again, if the sun's influence on a life form is very great then this life form allows the sun to think within it, to will in it—it does not become independent. Human beings are independent because they do not have this outer protection but are more or less exposed to their earthly environment. It is indeed interesting to note that animals are less dependent on the earth than humans are. Animals are largely created from outside the earth. I have provided evidence of this for you everywhere. But human beings are emancipated from these outside natural influences. And that is because they have an unprotected skin, as it were, in all directions, and must find their own protection.

Looking at the clothes we ordinarily wear you can see that there are two parts to them. One part is evident from the fact that in winter we put on a winter coat to protect us from the cold. This is the part of our clothing where we seek protection. But it is not the only part. You can see for instance, especially in women, that they look not only for protection in their clothes but also arrange them in a way they find beautiful. It may often be horrible, but it is supposed to be beautiful. This is a matter of taste or lack of taste, but it is meant to be beautiful, to adorn. These are the two functions of our clothing—to provide protection from the outside world and to adorn.

One of these functions has developed more in the north, where people need protection. There the clothing that is worn has more of a protect-yourself character. People actually do not go to great lengths when it comes to protection. But in warmer regions, regions where whole nations go about practically naked, really, the decorative aspect makes up the little, or if they put on more garments, the main part of their clothing.

You no doubt know that higher civilization has actually come from the warmer regions, that more of the life of mind and spirit has come from warmer regions. Considering the clothes people wear, we can therefore always see that in a sense the type of clothing designed to protect people from outside influences has remained imperfect. The clothing designed to adorn, on the other hand, has been developed in all kinds of ways. Now it is of course a question of people's taste, as you'll agree. The whole inner attitude of people comes into this. Let us think of more primitive peoples who are less sophisticated and more aboriginal. Such peoples have a great sense of colour. In our regions, where we are, of course, far advanced in intellect—or at least consider ourselves to be so—we do not have the sense of colour that the more aboriginal peoples have.

But those more aboriginal peoples also have a sense for something very different. They have a sense for it that human beings have supersensible, spiritual aspects. People in 'civilized' parts of the world no longer believe today that there are people who may not be as clever as civilized people consider themselves to be but have a sense for it that human beings have a supersensible aspect. And they sense this aspect in colour. That is how it is with those simple peoples, they sense that there is a supersensible aspect to them—I have called it the astral body—and sense its colours, and they want to make this invisible part of themselves visible. So they adorn themselves in red or blue, depending on whether they see themselves as blue or whatever in the astral sphere. This comes from the view of themselves that comes to these people from the world of the spirit.

The Greeks, for instance, saw that the human ether head is much bigger than the physical head, that it projects, and they therefore endowed the goddess Pallas Athene with a kind of helmet. But if you look at Pallas Athene and examine the helmet she is wearing you can see that the helmet has something like eyes at the top. You can see this everywhere; just look at Pallas Athene, even a poor quality statue, and you see eyes up there on the helmet. This proves to you that people believed it was really part of the body. It is something one is also able to see; they put it on Athene.

And the kind of clothing people created in regions where they had a feeling for the supersensible human being was made to show how they saw this human astral body.

Now in our regions—you know this, gentlemen—only ritual garments are arranged to be really colourful. If you look at the ritual garments, they are certainly arranged according to the way people saw the astral body with their inner eye. The colours used and the design of the garments basically derive from the supersensible sphere. And it is only if we understand this that we understand to what extent clothing is made decorative. This is also most important. If you look at pictures painted by the old masters you see that Mary, for instance, always wears a particular kind of dress and a particular kind of over-garment. This is meant to indicate the nature of her astral body, her heart and soul. This is meant to be indicated by her clothes. Compare pictures where Mary appears together with Mary Magdalene, you will always find that the old masters saw Mary and Mary Magdalene in a different light by the way they presented them, for this was thought to lie in their astral bodies, and the garments were painted to indicate the colour nature of the astral body.

We civilized people have entered more deeply into materialism, and no longer have a feeling for this supersensible aspect of the human being. We think with our earthly intellect and think the earthly intellect is master of it all. Indeed, gentlemen, this is also why we no longer have any feeling about dressing in a way that the clothes we wear would make us look at least half-way human! We put our legs—if we are men—into tubes. That is probably the plainest kind of garment you can have, this trouser tube! But we do much more; if we want to be particularly posh we stick a stove-pipe on our heads. Just imagine the face of an ancient Greek, if he were able to rise and someone would come towards him who has stuck his legs into two tubes and, what is more, has a tall stove-pipe up there, and what makes it even worse, in black! The Greek would not think this was a human being but an unbelievable spectre. This is something we must think about. And it even goes so far that one cuts away pieces of the coat, which is ugly enough as it is, and then calls it a tail coat. This is something which shows more than anything how thoughtless humanity has become. It is just because we are used to it, and, as I said, you are considered half a fool if not a complete fool if you do not join in, that we do join in with this. But we have to be aware that the whole way men dress today does rather remind one of a madhouse, especially when it is supposed to be utterly normal. It does show that people have gradually left all reality behind.

Women—and many men used to think they were less civilized than men—have adhered more to the original ways with their clothing. But there is a trend today to make women's clothing more like men's clothing, only it has not quite worked out so far.

To adorn—what does it mean, really? To present oneself outwardly in such a way that one also gives expression to what the human being is in spirit! To see how everything connected with clothing developed in more aboriginal nations we have to realize, in this respect, that among those aboriginal nations people did not feel themselves to be as independent as people today feel themselves to be independent. Today everyone feels himself an independent person, quite rightly so in some respects. Now you see, he will say to himself: 'I have my own mind and use it to think of everything I am able to do.' If he is particularly conceited, he will immediately see himself as a reformer, and so we have almost as many reformers today as there are people in the world. People thus consider themselves to be absolutely individual. No such thing existed among earlier peoples and tribes. Those tribes saw themselves to be at one as a group, with a spiritual entity their group soul. They considered themselves part of the group, like the members of a body, and the group soul was to them the element that kept them together. Within this group sphere they thought themselves to have quite a specific configuration, and they brought this to expression in the clothes they wore. So if they thought of their group soul as having a helmet-like extension to the head, as in Greece, for example, they would wear a helmet (Fig. 12). And that helmet did not develop from any need for protection, but because people believed they would be more like their group soul if they wore a helmet.

In the same way some group souls were thought to be eagles, vultures or other animals, owls, and so on. People then organized their clothing accordingly, decorating it with feathers or the like, so that they would be similar to the group soul. Clothes thus evolved largely to meet the spiritual needs of people.

Among the aboriginal nations and tribes the clothes showed a little bit how they imagined their group soul to be. And when you find an aboriginal nation and ask yourself how they dress, and above all adorn themselves, do they adorn themselves with feathers or an animal skin, you can say that if you find a tribe that adorns itself mainly with feathers, you know their common group soul, their guardian spirit, as it were, was thought to be a bird. If you find that a nation adorns itself mainly with animal skins, they imagined their group soul, their guardian spirit, as it were, to be a lion or a tiger or something of this kind. We can therefore find out something about the original clothes people wore by asking ourselves how those people envisaged their group soul.

And Mr Burle was quite right when he said that some wear floating garments, others close-fitting ones. Floating garments evolved because people wanted to make bird-clothes, garments with wings; it pleased them to have something winglike. And it actually had a great effect on people's skill development to acquire such floating garments. And when they rotated they would also make pleasing movements with their arms. This made them skilful and so on. So we may well say: to adorn oneself is to have the will to bring something spiritual to expression in the clothes worn at the time. And merely to protect oneself and this is not, of course, to say anything against it—gives expression to the uninspired aspect of the human being. The more one seeks to use clothes that serve only to protect, the more one is lacking in inspiration. The more one seeks to adorn oneself, the less does one lack in inspiration, really wanting to give expression to the spiritual quality to be found in the dignity of man.

It is perfectly natural that these things shifted completely in later stages of civilization. We have to be clear about the following, for instance. Imagine those early peoples discovering that the sun has a special influence on the human heart, the human chest altogether, and saying to themselves: 'I am a person with heart only because the sun is able to have the right influence. Not outwardly, on the skin, for then I would be completely hairy, but when they are inwardly digested, the sun's rays act on the heart.' The heart is quite rightly seen in relation to the actions of the sun. What did people do who still were very much alive to knowledge of this connection with the sun? Well, you see, they tied a kind of medallion around their necks, a medallion representing the sun (Fig. 13). They would wear this to say: 'I make it known that the sun has an influence on the heart.'

Later on this would be forgotten, of course. Civilized people have forgotten that this was originally a sign that the sun has an influence on the heart. But something which once had meaning has become habit, truly a habit. And people then put on such things from habit, no longer having any idea why it was worn originally. Such habits develop first of all; later governments lay claim to them, making them their possession. This is essentially all there is to the so-called 'advancement' of states and governments—they take possession of things that have become habit. Someone discovers—only a human being can discover it—a medicine, let us say. This arises from his mind and spirit. The government then lays claim to this medicine for itself, saying: 'It may only be sold in one place or another with my permission.' In the end, therefore, it comes from the government.

That is also what happened to the sun medallion. People originally created and wore it from personal knowledge, and later out of habit. Then the governments said: 'Oh no, you cannot do this of your own accord, but we must first give you permission to create and wear it.' And that is how medals and decorations developed. Today governments adorn their adherents with medals. Medals have of course lost all meaning by now. But anyone who grumbles about medals and decorations should also know that they did have real meaning originally, that they have evolved from something that had meaning.

You see, that is what has happened with many of the original garments. The ancient Romans and Greeks still knew that if they went about showing their naked bodies that would not be the whole human being, for there was also a supersensible body. They imitated this supersensible body in the toga, and that is how the toga was created. The Romans therefore wanted to reproduce the supersensible body. The toga is nothing but the astral body. And the folds so skilfully made in the garment showed the forces of the astral body. People of modern times, no longer having any knowledge of the real spiritual human being, knew no better than to take the old garments and, in order to have something new, cut off little bits here and there, first shortening the part that came close to the ground, and then making it as far as possible a garment you could slip into, and gradually changing it until it had become the modern man's jacket. The modern man's jacket is nothing but the chopped-up toga of old, only one does not recognize it as such.

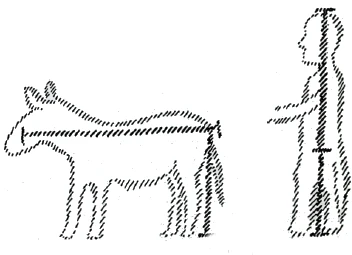

Take belts, for instance. Now, the belt developed because people knew they were divided off in the middle in a way no animal is divided. No animal has the kind of diaphragm that human beings have, for example. And this division in the middle does not have the significance in any animal which it has in human beings. Just look at it and compare. People are forgetting about this today in the most incredible way. So they often compare the length of a person with that of an animal in order to establish something or other, for instance how much food an animal and a human being needs. But just think: there you have an animal, and there a human being (Fig. 14). Someone measures the length of the animal and the length of a human being. Well, gentlemen, can we compare the two? That is nonsense. The length measured in the animal is only this part in the human being. You can therefore only compare the length a person has from the top of the head down to the lumbar part, here, to compare it with the animal world. Or if you want to compare this part of the human being with the animal you can compare it with the two hind limbs of the animal. It is really true that thoughtlessness often goes a very long way.

Now when primitive people became aware of the significance of this division which humans have in the middle, they indicated this with a body belt. So here, too, a human property was indicated, by the body belt.

And you see if the nature of the human being is truly recognized, one will know, for instance, that a special power actually relating to thinking lies in the crook of the knee. And the crook of the knee was therefore adorned—we can no longer decorate it specially today because it is covered by the trouser tube. This later became the Order of the Garter in the way I have described. All these things have evolved from genuine perceptions; they did not evolve in the terrible kind of abstract, theoretical thinking we have today.

And you see, modern clothes have also lost all their colour. The question is, why did they lose their colour? Because one's feeling for the supersensible is best expressed in colour. And the more people delight in colour, the more are they really inclined to grasp the supersensible in some way or other. Our age likes grey in grey, however, colours that are as colourless as possible. The reason for this may be indicated by the saying: 'When candles are away all cats are grey.' For modern people no longer look into the light at all, I mean the light of the spirit. Everything has become grey for them. And they show this most in their clothes. They no longer know what colour they should use to adorn themselves, and so they do not adorn themselves with any colour. One can really see that everything by way of clothing is connected with things people still knew in the past, when they knew about the supersensible human being. And civilization in general has turned grey. But for some purposes in life the original colourful nature has remained, though people do not know where it comes from.

The kind of clothes our military people wear in a modern nation have of course developed at a time when people increasingly needed to defend themselves. And you can examine every part of military clothing to see if it has some connection with means of defence or attack. Basically we may say that all military clothes are really obsolete today, for one no longer understands them. You see, the jacket of a modern suit can be understood, for it has developed out of the Roman toga. But a military uniform coat can only be understood if one explains it not in terms of a Roman toga, with its folds, that has been distorted into caricature, but out of medieval knighthood, when the whole was a kind of cuirass. The cuirass has been reshaped.

Flags were also mentioned (as part of the question). You see, the situation concerning flags is this. Originally the heraldic animal would be depicted on the flag—it need not necessarily have been an animal. But what was this animal? It was the group soul, the soul that kept people together. And they wanted to have an image of it before them when they were together as a group. They made it into a flag. And flags actually are proof that common ideas people had were used to create their flag.

Here it is particularly important to be clear in our minds that the old masters were much closer to reality in their work than modern painters. Today people paint pictures which are framed and hung somewhere because that is what one has got used to. Basically it is meaningless. Why should one hang a picture on a wall? That is the question we must ask. In earlier times it was like this. People had altars, and they painted the image on the altar that should come to mind when one stood before the altar. They had churches, and people walked about in them. On the walls they painted the things that should come to mind one after the other as one walked around. This had meaning. It related to what went on in people's minds.

And in the knights' castles of old—well, what was the knighthood based on in those days? It was based on the fact that its members always looked up to their ancestors. The ancestors were more important to them than they were themselves. Someone who had a great many ancestors counted more. And so they would hang up paintings of their ancestors. And again it had meaning.

It was only when this meaning was lost that landscape painting evolved. And landscape painting—to have a landscape hanging on your wall, well, you know, it is something people may like. I do not want to be at all horrible in this respect and decry all landscape painting, but you have to accept that a painted landscape can never be the same as when you go out into the landscape yourself! And landscape painting really only began to develop when people no longer had any real feeling for nature.

If you look at paintings done just a few centuries ago—yes, take a look also at paintings by Raphael or Leonardo14Raphael Santi, 1483-1520. Leonardo da Vinci, 1452-1519.—and you'll see that they painted people. The landscape is just hinted at, quite childlike really, because people agreed that landscapes should be looked at outside, in nature. One can, however, bring a great deal to expression in a human being; man is not just nature, and one can bring different things to expression. And so Raphael was able to bring much to expression in Mary. You may know the painting that is in Dresden—Mary with the Jesus child on her left arm, with clouds above. And then there are two figures down below—Pope Sixtus IV and St Barbara. This is the painting known as the Sistine Madonna. Well, gentlemen, Raphael did not paint this picture so that it might be hung somewhere but he actually only painted Mary with the Jesus child so that a banner might be made to be carried ahead of processions. They had these processions where people go out into the fields to an altar, and they always had a banner that was carried before them. They would stop at the altar, where people would kneel down. Later on someone added the saints Sixtus and Barbara. They do not at all belong in the picture, and the quality of the painting is terrible compared to Raphael's own work. But people don't notice this. Some admire the somewhat repulsive figure of Barbara in this painting just as much as they admire what Mary and the Jesus child themselves are!

All these things show you that people have moved away from the things that gave meaning to painting. Why did Raphael paint this picture for a church banner? Because people were to have this common idea as they went in the procession—which was in accord with the feeling out of which flags and banners were actually produced.

Then the desire arose to give at least some kind of meaning to things that have come down to us from earlier times, when they did have real meaning. Going to some places today, to Finland, for instance, you will see people wearing the old clothes again. People who especially want to be members of their nation wear the old garments again that had been forgotten and are now brought back again.

But people no longer live in the times when the old instincts were there that gave those clothes their meaning. Today we would have to find a way of dressing that arises from the life of mind and spirit we have today, just as those earlier peoples found their way of dressing out of what lived in their minds, out of what they felt to be the right way of dressing, considering the world and the human race. But people are no longer able to do this today because they know nothing of the real—that is, the spiritual—human being. And so it has happened that we wear garments today that really are quite meaningless and simply come into existence merely because meaninglessness is taken to extremes.

People originally wore belts to show that this was a special area. The belt was used to express this. Later on, people saw the belt, say that the person was divided at that point; they then made this division themselves using a belt. Instead of expressing something, the belt often made women's garments such that they did not express something but tremendously compressed the liver and the stomach and all kinds of things here. It is fair to say that much of what has developed in the materialist age has developed from lack of meaning, in utter meaninglessness. Things we have to recognize as nonsense today did have a particular meaning among primitive peoples. Let us assume, for instance, that some wild tribes have the peculiarity that they do not clothe themselves by pulling on garments but in some other way. A garment is really something, you'll agree, that adorns, adding something to what the human being is. The significance of the garment is really suggestion, revelation. The invisible is thus to be revealed in the garment. And the wild tribes thought—they still do so today, and so do other people—one does not necessarily need fabrics to clothe oneself, one can also dress by making all kinds of drawings on the body. They adorn themselves by tattooing, as it is called. People thus make all kinds of marks on their bodies.

Well, gentlemen, those signs which people drew on their bodies originally had great significance. Let us assume, for example, someone scratches a heart shape on his body. This has no significance when he is awake, walking about during the day. But when he is sleeping, this heart scratched into the skin makes a highly significant impression on the sleeping soul, and becomes a thought in the sleeping soul, a thought he will of course have forgotten when he returns to conscious awareness in the morning. Tattooing therefore originally developed out of the intention to influence the human being even in sleep. This, too, lost significance later, even among primitive peoples, at least to the extent that people do it only from habit, continuing out of habit, but it has lost its meaning.

Now you see, you have to take all these things into account. You will then see that clothes developed partly from a desire for protection, and in the main part, most of all, from a desire to adorn oneself. And this adornment has to do with people making the supersensible outwardly apparent. And it then happened specifically with regard to clothing that people gradually knew no more than that one wears them. And that is how national costumes developed. Obviously people for whom there was greater necessity to protect themselves would have close-fitting garments, thick garments, weighing the whole body down, more or less, with garments, or at least the parts that were more exposed to the cold. Someone living in a warmer climate would develop the decorative aspect much more strongly, would be wearing thinner garments, floating garments, and so on. It would to some extent depend on the whole environment, on the climate, how people partly protected and partly adorned themselves. Then people forgot about this. When tribes began to migrate it could happen that a people coming from a region where the clothing was appropriate to the region moved to another region where one really could not see why this kind of clothing should be suitable for these people—but they kept them from habit. And so it is often very difficult today to discover why people wear a particular kind of clothing by just considering their immediate environment. And we can see, can't we, that people are simply no longer thinking. They are like a polar bear who is given a white garb because this does not stand out much from the snows in the Arctic and therefore means protection from pursuit and so on. Well, if the polar bear were to wear this in a warm climate it clearly would not offer protection!

That is the way it is altogether. People stick to the things they are used to without being fully aware of their meaning. Because of this it is not so easy today to know from the way people dress why a particular nation dresses in a particular way. As I said, we have to go back to earlier times for this.

You'll find, for instance, that the Magyar costume worn in Hungary is something quite special. The Hungarians wear fairly high boots with narrow shafts, close-fitting trousers inserted in those shafts, and a jacket that fits closely. Everything has been modernized, has lost its original meaning, but it indicates something that is also evident in the Hungarian language, for its original terms are largely hunting terms. It is really strange. If you go to Pest, for example, you may, as you cross the road, see a sign that says: Kave Ház. This is nothing other than 'Coffee House'! It is not Hungarian or Magyar, of course, but comes from the German Kaffeehaus, with just minor changes. People will say Kave Ház without realizing that it is really a German word. But if one leaves aside the many words coming from the Latin or German in Magyar, one realizes the language consists largely of hunting terms, and that the Magyars were originally hunters. And if you consider the costume, you see that it is a style that was originally the most comfortable for hunters. It then came to be modernized and changed. There you can still understand it, at a pinch. But when one sees the clothes people wear today, one cannot understand anything very much.

Now, Mr Burle, have some things become clear with the things I have said?

Mr Burle: Fairly!

Now, we'll continue with the lectures next Saturday. Perhaps the one or the other of you will still think of something you'd like to ask.